Football has been my favorite sport since I can remember having a favorite sport or knowing what sports were. I can still remember watching Joe Namath and the Jets upset the Colts in Super Bowl III. I was five at the time. It wasn’t the first football game I’d watched, but it was the first one I’d watched from beginning to end. Many, many more would follow.

But, this was 1971, and, in 1971, football season was not the monster it is today. Major colleges played 10 games and there were no such things as conference championship games. There were a dozen bowls and the season ended on January 1st. The NFL hadn’t come up with the concept of the twelve-month calendar, keeping the league in the news year-round. The 1970 season had ended with the Super Bowl on January 17th. The draft was held two weeks later, and the league then shut down until July when training camps started. Of course, the NFL preseason was worth watching in those days, since starters actually played and the games were often a lot of fun.

The first was always “The College All-Star Game”, which was played in Chicago and featured the previous year’s NFL Champion against an all-star team of picks from the previous NFL draft. The game was played from 1934 until 1976 (with the exception of 1974, when it was cancelled by a strike), and the fact that it took folks over 40 years to figure out just what a terrible idea the game was (Seriously, you want to send your top rookies, guys you hope can help you in the coming season, to a training camp where they won’t learn your schemes or playbook all in the service of risking injury in a meaningless exhibition game?) is only slightly more astounding than the fact that the game survived into its second season after the first game ended in a scoreless tie. (A total of 25 points were scored in the first four games combined.) The game shuffled off this mortal coil after the 1976 contest in which the Pittsburgh Steelers mugged the out-classed all-stars (The starting QB for the college team was Mike Kruczek, who would become Terry Bradshaw’s back up and inspire so much confidence in the Steelers’ coaching staff that, when Kruczek was forced to start six games for an injured Bradshaw, the team threw the ball exactly 85 times. In six games. Among those 85 tosses were three interceptions and not a single touchdown pass. Kruczek played four more seasons before retiring. And, to this date, he STILL hasn’t thrown a touchdown pass. But, I digress.) for nearly three quarters. At that point, high winds prompted Ara Parseghian, who was coaching the All-Stars, to call time out. Fans, who’d been sitting in a heavy rain all night, took this as invitation to run onto the field and begin sliding around on the artificial surface. (I am not making this up.) With the rain coming down even harder, the officials ordered the teams to their locker rooms. The fans took this as an invitation to continue running around and sliding on the turf…before tearing down both goal posts. (Keep in mind, this was DURING the game and, no, I’m STILL not making this up.) With the goal posts down and the field conditions atrocious due to the continued downpour, Pete Rozelle finally made the decision to call the game. This led the fans still in the stands to, basically, riot, pouring onto the field and starting several brawls. (Nope, still not making it up.) I am also not making up the fact that none of this convinced Chicago Tribune Charities, which had been sponsoring the game since the 0-0 thriller in 1934, that the time might be nigh to put an end to the contest. The organization planned to hold another game in 1977, but, cooler heads (and rising insurance costs) prevailed and The College All-Star Game went the way of the single wing, making The Hall of Fame Game the new preseason opener (when, you know, the field is painted properly.) But, again, I digress.

The point is that, even counting the preseason, which began at the end of July, there were six full months without football, and, as most of those months fell in the summer, well, that meant baseball ruled my sporting world from April through mid-September, when college games began and the NFL games began to count. And, the team that ruled my baseball world was, of course, the Pittsburgh Pirates.

In 1971, most of my sports heroes wore the uniform of the Pittsburgh Pirates. There was Roberto, of course. And Willie. And a personal favorite, Al Oliver, a guy whose swing remains the sweetest I’ve ever seen in 40-plus years of watching the game. And, unlike my football heroes (and, I had a few), Roberto and Willie and Al weren’t just around once a week. They were with me every day, every day from April through September. Now, they weren’t often on TV, because this was, again, a different era. (How limited was TV coverage of the team in 1971? Well, let’s remember that there were several scheduled doubleheaders a year in those days, and KDKA, the television home of the Buccos, engaged in the strange practice of showing HALF a doubleheader. No, I’m not making that up, either.) But, the radio had the Buccos on it almost every day, and that was especially wonderful in the summer when, obviously, we didn’t have to deal with school and school bedtimes.

Now, this isn’t to say we didn’t have a lot to do in the summer. We did. Lots and lots of fun stuff. But, there were plenty of hours in the day, hours that were usually taken up by school, homework, and such, to fill. And, baseball on the radio was a great way to fill it. Of course, I didn’t listen to every game. Sometimes other things got in the way. But, I listened to a lot of them and even kept score of some. (I learned to do this at a young age and have always enjoyed it. I never, however, got as good as my great aunt, who scored every single game all year in a special notebook that also contained space for all the out-of-town scores, which she recorded faithfully by often listening to a radio late at night and picking up games from as far away as Los Angeles…and, no, I’m not making that up either. Want to know what Willie Stargell did on May 7th? My aunt could turn to the page, tell you that Starg went 1-4 with a solo home run in the Buccos 3-2 victory over the Dodgers in Los Angeles and that the homer came in the sixth off Don Sutton. She could also tell you that Mudcat Grant threw two perfect innings in relief to get the save, and, by the by, the scores of every other game that took place in The Majors that day. But, I digress once again.)

The point is that the 1971 Pirates weren’t just my heroes, they were my companions on many a summer day and night. I can still, to this moment, recite the everyday lineup from memory. Manny Sanguillen catching. Bob Robertson at first. Dave Cash at second. Jackie Hernandez, who’d come to the team in a trade the year before, at short, subbing for the injured Gene Alley. Richie Hebner at third. In the outfield, Stargell in left, Oliver in center, and, of course, the Great Roberto in right. Every day, whether I watched the game, listened to the game, or simply read about the game in the paper the following day, I followed the Buccos, followed as they slowly pulled away from the field in the NL East, followed and began thinking about another chance to win the NLCS, which the team had lost to the Cincinnati Reds the year before.

And, I wasn’t the only one. Lots of the guys I hung around with followed baseball and the Pirates, and they all loved the team. A lot of them collected baseball cards like I did and prized their Pirates. A lot of them chose various Pirates to portray during our endless summer whiffle ball games. (Nobody could be Clemente if John Stumpf was playing. John was ALWAYS Clemente, and any attempt to change this would devolve into a near fist-fight until someone would yell, “Oh, let him be Clemente and let’s PLAY!” Every. Single. Time. It got to the point where no one would be Clemente even if John weren’t playing, on the off chance he’d show up and join the game in progress. Yep. Digressing again.) So, you can imagine my surprise when, one fine day as school approached, as our time playing whiffle ball and football on the street were about to be reduced to weekends and as much time as we could steal after school, some folks began talking smack about the Buccos. A few of the guys, the guys who’d been pulling for the team and portraying various Pirates in our games all year said they’d never root for them again.

Now, fans turning on their team is something that happens in sports. The main culprit is usually a long period (or, in the case of some fans, a short period) of losing. Other things can have an effect, too, though. Some Packers fans turned on the team after it parted from Brett Favre. Some Cowboys fans did the same after Tom Landry was fired. Some Browns fans never returned to the team after it left Cleveland for Baltimore. (Those, by the by, have been, to this point at least, the LUCKY Browns fans.) The Pirates saw the city turn on them twice in recent decades, once in the 80s with the drug trials and again during the 20-year losing streak. (And, a third instance may be underway.) So, it happens. But, what happened here was a different animal.

The 1971 Pirates weren’t losing. They were in the process of winning 97 games. They weren’t leaving town or involved in a scandal, and they weren’t parting with a popular player or manager. No, the Pirates transgression was different. See, Robertson and Hebner weren’t available on September 1, 1971. So, the team moved Cash to third base and slotted Rennie Stennett in at second. Meanwhile, Oliver moved to first to replace Robertson, and, with left-handed Woody Fryman pitching for the Phillies, Gene Clines got the start for Al in center. Doc Ellis started the game on the mound for the Pirates. Now, if you don’t know those Buccos like I do, you may not understand the significance of those moves. If you do, you know. The Pirates became the first team in the history of major league baseball, which went back exactly 100 years at that point, to start nine black players. And, that was enough for some people to start hating them…even though the starting nine played exactly one and one-third innings. (A wild Ellis walked four and was pulled for Bob Moose in the second. The other eight guys, however, were doing plenty of damage, blasting out Fryman and scoring nine runs in the first three innings.)

To say I was shocked at some of the stuff I was hearing about my team would be an understatement. At the dinner table, I brought it up to my father, who was quite the baseball player in his day and instilled in me my love of the game. “Some guys say they hate the Pirates now, because they played nine black guys yesterday.” Dad: “Yes, and they won the game. I hope they play nine black guys tonight, too.” They didn’t. The next day, Alley played shortstop and Steve Blass pitched. The Bucs lost to the Expos. Shortly, Hebner and Robertson returned to the line up and the team rolled to the NL East title by seven games over the Cardinals. And, that meant the NLCS for the second year in a row.(The 1971 NLCS was only the third in history, by the by, and the Pirates became the first team to qualify twice.)

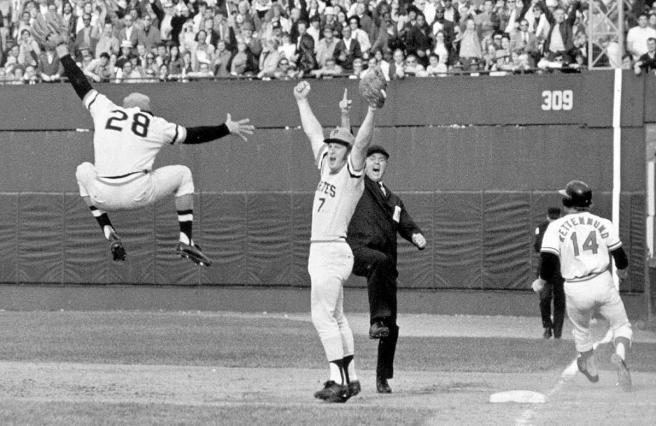

The Pirates lost the opener to the Giants in San Francisco, then ran off three straight wins, wrapping the series with back-to-back victories over future Hall of Famers Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry. The World Series didn’t start any better than the NLCS had. The Bucs lost two in a row in Baltimore, and the joke was that the team was like an elephant. It was coming home to die. Not so much. The Pirates won three straight at Three Rivers, and, after the Orioles pulled out the sixth game in the tenth back in Baltimore, well. It was time for the Great Roberto. Clemente homered to put the Pirates in the lead in the final game, and Jose Pagan doubled the lead by doubling in Stargell in the 8th. I can still see Willie steaming around third and heading toward the plate, the look on his face telling Orioles catcher Elrod Hendricks, “Don’t be there when I get there, Elrod.” Elrod wasn’t there. The Orioles scratched out a run in the eighth, but the ninth ended with Blass leaping into the arms of Robertson, and a lot of guys who stopped loving their team looking for room on the bandwagon.

I can still picture the team. Sangy. Robertson. Cash. Hernandez. Hebner. Willie. Scoops. The Great Roberto. And, I can still picture that other team, too. The one that played only an inning and a third together, and found out that’s all the longer it took to make history. I can also still see my Dad at our table. “I hope they play nine black guys tonight, too.” Because, no matter how old you get, you don’t forget your heroes.