It was 10pm at Charlie Law’s funeral home in Baltimore. That was the hour the business traditionally closed. But, there was still a line stretching two blocks long outside the doors, people who’d been waiting for hours for a chance to say a final goodbye to the man whose body was lying inside. Law needed to ship that body to Detroit for burial the next day. He was running out of time. He called Geraldine Young, the woman who’d made the funeral arrangements, and asked her what to do. “If the people are there, Charlie, let them see him,” Geraldine Young said. The people were there, more than 20,000 of them in total. So, Charlie let them see him.

The man to whom they’d come to pay their respects was not a head of state or some famous star of stage or screen. He’d been born into a family of cotton pickers in Uniontown, Alabama 31 years before. That man had never known his father, who’d fallen ill and died in a federal Civilian Conservation Corps camp. There’d only been his mother. When he was three, she had moved him for the first time, to the same city where he’d be moved for the last time, Detroit. They’d lived on the East Side, in a ghetto called Black Bottom. Until he was eleven. He’d been making breakfast for himself that morning, the morning a policeman arrived to tell him his mother was gone. She’d been stabbed 47 times by her boyfriend and had died in the street.

Where he got the pictures of his mother, no one knew. But, he had them. And, he carried them around with him. Black and white photos. But, not posed shots of a smiling woman. Not pictures of his mother at a wedding or some sort of happy gathering. No, pictures taken by a homicide photographer at the scene of her death. Macabre photos. Images no doubt burned into his brain. Images that, perhaps, explained a lot.

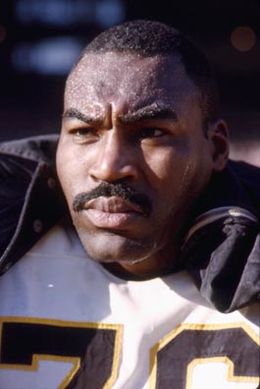

Explained, maybe, why he was afraid all the time. Afraid? He was 6’6” tall and weighed 306 pounds. He wore size 56 suits and had huge hands and arms and a seven-foot wingspan. He was so strong that he was seen lifting a piece of cannon that weighed 41 pounds…with his fingertips. He cut about as imposing a figure as you can imagine. What could a man like that be afraid of?

Something. He was known to slide his bed against the door before he went to sleep so that no one (nothing?) could get in. He slept with a gun under his pillow. And, there was the dog. For awhile, he had a roommate who owned a huge dog. He’d tie that dog to the end of the bed at night before he went to sleep. More protection against…something. No one knew what. But, something so frightening that, even with all the precautions, sleep was still sometimes impossible. So he’d pace nights away. And, it wasn’t just the nights. Sometimes, during the waking hours, he’d break down into tears for no apparent reason. Haunted. Day and night.

After his mother’s death, he moved in with his maternal grandfather. He always insisted the old man had loved him, but, it was tough love. At eleven he was required to buy his own clothes and pay room and board to his grandfather. He got a job. Which was no big deal. He’d been working setting pins in a bowling alley even when his mother was alive. While with his grandfather, he washed dishes, worked at a junkyard, loaded trucks, even worked a midnight shift at a steel mill, coming off shift at seven and changing clothes before going to school. Tough love. The old man didn’t believe in talking things out. Instead, he screamed at the boy and whipped him. Once, he tied his grandson to his bed and stripped him before beating him severely over a stolen bottle of whiskey.

Demons, then. Demons of the most dangerous, strongest, most intractable type…the childhood kind. Demons that haunted him right up until the day of his death. Demons built of the stuff we’ve already talked about, and other things. Things like the fact that he was 6’4” and 220 pounds in sixth grade, “a freak” in his own words, who needed a special desk and was always wearing clothes that were too small, since he kept outgrowing whatever he bought. Other kids tormented him and called him stupid.

The one respite was sports. In high school, he learned to play football and basketball. And, he was good. But, that was all taken away when a rival coach found out he was playing semi-pro basketball and softball. He was declared ineligible for sports his senior year. Then, somebody did the kid a favor. Finally. His football coach advised him to drop out of school and join the Marine Corps. And, the big, directionless kid turned into man with a future. And, that future was in the sports denied him in high school.

He became a star on the football team at Camp Pendleton. He was 6’6” tall and 267 pounds by then, but, despite that size, he was one of the fastest men on the team. Somebody was bound to notice. And, that someone happened to be a public relations director for the Los Angeles Rams. Guy named Pete Rozelle. Rozelle advised that the Rams sign the big Marine, and the team did so.

His years with Los Angeles were not great ones. He was far from a finished player, having never played in college, where he’d have learned the fundamentals of the defensive line position he was playing professionally. Opposing linemen took advantage of his poor technique making him far less effective than he could have been with the awesome physical gifts he had. And, things off the field were worse.

He had two major weaknesses, booze and women. He consumed copious amounts of the former, and went through the latter so quickly that he was once married to two at the same time. The pursuit of those two weaknesses often led to him staying out all night and sleeping in the back of a teammate’s car on the way to practice the next day. He was also known to fall asleep in meetings, leading coaches to pound on metal drawers to awaken him. After two years, the coaches gave up on him and he was released. Baltimore signed him for $100. It would be the best money the Colts franchise ever spent.

With Baltimore, it was all different. Like the Marines, the Colts provided a structured environment, and the team’s defensive line was full of talented veterans. In those days, there was very little positional coaching, so the linemen would get together on the field and show one another tricks and techniques they’d developed. The new guy lapped it up. For the first time, he learned to play football. And, when he did, look out, world.

Today, bad football announcers who resort to clichés often call players “a throwback”, meaning, of course, that a player’s style recalls an earlier era. Well. The big man was a “throw forward”, because he was something that had never been seen before, a huge man who could run. He was so fast, he could cover running backs or tight ends on pass patterns, and Colts coaches considered making him a linebacker. They didn’t, though, because they couldn’t replace him on the line, where his game was pursuit, sideline to sideline. He did it like no man his size had ever done it and like few ever have to this day. If you saw a young Joe Greene, that’s what you were dealing with.

Just two years after being cut by Los Angeles, he was an All-Pro in Baltimore starting on two consecutive NFL Championship teams for the Colts. And, while he was huge and ridiculously strong, he was always careful not to be nasty or dirty on the field. In fact, he often picked up players he’d tackled, leading teammate Art Donovan to shout during one game, “Let them get up themselves.” He only shook his head and said, “I don’t want people thinking I’m mean.”

He was not mean. He was the furthest thing from it. But, he was physical. He once stopped a 225-pound fullback, running at full steam, simply by sticking out one mammoth arm. The fullback went flying backward. Several people have been credited with developing the head-slap, a since-outlawed technique that defensive players used to use on offensive linemen, but the big man’s head slap may have been the most feared in the history of the league. He’d take one enormous hand and slap it flat against the earhole of his opponent’s helmet…if that opponent were holding. And, if said opponent complained about dirty play, he’d simply say, “If you stop holding, I’ll stop slapping.” They often stopped holding. (Oh, and Bubba Smith became famous, on a beer commercial, for the line, “I used to grab the whole backfield. Then I threw guys out until I found the ball.” Well. That line was originally uttered by the big Marine, who said, “I just reach out and grab an armful of players from the other team and peel them off until I find the one with the ball. I keep him.”)

Physical. But, not mean. He once gave his bed to a homeless man who’d passed out drunk during a driving Baltimore snowstorm. And, children. Several times, he stopped his car when he saw a kid running barefoot in the winter. “Why don’t you have shoes on?” he’d ask. And, if the child, as some did, explained that he didn’t have any shoes, well. He’d get himself a ride home from the big Colts lineman. And a ride, with his mother, to a clothing store, where shoes and other items of clothing would be purchased for the youngster. Ex-teammate Johnny Sample says he saw the big man do that not once, but three or four times during his career with the Colts. “Heart of gold,” Sample said.

That Colts career, successful as it was, surprisingly ended after the 1960 season. Baltimore didn’t make the championship game that year, and, in the offseason, the team traded their 29-year-old star defensive lineman to the Pittsburgh Steelers in a five player deal that brought wide receiver Jimmy Orr to the Colts. Coach Weeb Ewbank said the team had to include the big Marine in the deal to get Orr, but assistant coach Charlie Winner says he was included in part because of his off the field problems, which, by then, also involved legal issues related to child support.

The Steelers, in those days, had some players who didn’t mind doing a little drinking, so the new defensive lineman fit right in. He was often found at the South Park Inn, where quarterback Bobby Layne would buy the drinks. Often, the new guy got an entire bottle of VO. And, if he didn’t slow down on the alcohol, he didn’t dial back on the ladies, either. One teammate who used to pick him up in the mornings to drive him to practice claims he often found multiple women on the scene. In various stages of undress.

On the field, though? The big man still dominated. He made the Pro Bowl in 1963, and, in that game, one that was taken seriously in those days, he turned in one of his best ever efforts on the gridiron, being named one of the game’s MVPs. Along with a guy named Jim Brown. That game, however, would mark the last-ever professional football appearance for the kid from Uniontown, Alabama.

On May 9, 1963, the big man was in Baltimore, where he lived in the offseason. He’d begun an effort to reunite with his first wife, and he saw her that afternoon in a record store. He told her he was pitching in a softball game that night. She never saw him again.

There’s no reliable account of what happened after the softball game, since the only account came from a heroin user with a lengthy criminal record named Timothy Black. Black claimed that the big Marine picked him up on a Baltimore street corner, and, after they picked up two women and partied until 3am, they went out to buy some heroin, at the Marine’s insistence. Black claims to have cooked the heroin and injected his “friend” with a dose of it. But, something went wrong. The big man fell unconscious, Black claims, and efforts to bring him around, including injections with a saline solution, failed. They called an ambulance. It didn’t matter. The Big Marine never regained consciousness. He was dead of a heroin overdose at age 31.

Black’s story, again, is not reliable, and for several reasons. The first is that he claims his “friend” had been shooting up heroin three times a week for six months. But, an autopsy revealed only four fresh needle marks on the big man’s body, accounted for by the heroin and saline injections, and one old one, likely left by a blood test. This was hardly the body of a junkie who’d been using heroin regularly for half a year. Making the story even less likely is the fact that everyone who knew the big man knew he had an overpowering fear of needles. He also showed no signs of drug use while he was alive.

So, what happened? It’s likely no one will ever know. Black took whatever he knew to the grave two decades ago and the case has been closed since 1963. But, questions remain. Did Black give the big man the fatal dose accidentally or was he trying to render him unconscious to steal his money? Follow the money, said former teammate Buddy Young, who said the ex-Marine had $700 with him when he left that night. Only $73 was found on his body.

Eventually, the rest of the crowd made it through the doors of the Charlie Law’s funeral home and the body was sent back to Detroit. Over one thousand people showed up for the funeral. The casket was carried by eight top NFL players, Erich Barnes, John Henry Johnson, Dick “Night Train” Lane, Lenny Moore, Jim Parker, Don Joyce, Johnny Sample, and Luke Owens. That coffin was draped in an American flag, reminding all those people of its occupant’s service in the Marine Corps. And, when the ceremonies were over, when the preacher had summed up a life, and just about every life ever lived, in one sentence, “He did some good. He did some wrong,” the big man was laid peacefully to rest in a midnight blue suit and a white silk tie. And the demons that haunted the too short life of Eugene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb were vanquished once and for all.